Which of the Following Can Be Concluded From Harry Harlow's Research With Rhesus Monkeys?

| Harry F. Harlow | |

|---|---|

| Built-in | Harry Frederic Israel (1905-ten-31)October 31, 1905 Fairfield, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | December six, 1981(1981-12-06) (aged 76) Tucson, Arizona, U.Southward. |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Reed College, Stanford Academy |

| Awards | National Medal of Science (1967) Gold Medal from American Psychological Foundation (1973) Howard Crosby Warren Medal (1956) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychology |

| Doctoral advisor | Lewis Terman |

| Doctoral students | Abraham Maslow, Stephen Suomi |

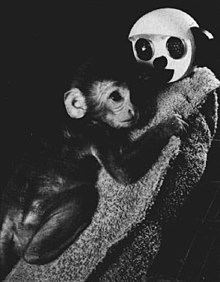

Monkey subject area is budgeted to the cloth mother surrogate in fear exam

Harry Frederick Harlow (October 31, 1905 – December 6, 1981) was an American psychologist best known for his maternal-separation, dependency needs, and social isolation experiments on rhesus monkeys, which manifested the importance of caregiving and companionship to social and cognitive development. He conducted nearly of his enquiry at the Academy of Wisconsin–Madison, where humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslow worked with him for a short period of time.

Harlow's experiments were controversial; they included creating inanimate surrogate mothers for the rhesus infants from wire and wool. Each infant became fastened to its particular mother, recognizing its unique face and preferring it above others. Harlow adjacent chose to investigate if the infants had a preference for bare-wire mothers or cloth-covered mothers. For this experiment, he presented the infants with a clothed "mother" and a wire "mother" nether ii conditions. In i situation, the wire mother held a canteen with nutrient, and the fabric mother held no food. In the other situation, the cloth mother held the bottle, and the wire female parent had nothing. Also later in his career, he cultivated infant monkeys in isolation chambers for upwardly to 24 months, from which they emerged intensely disturbed.[1] Some researchers cite the experiments as a factor in the rise of the beast liberation movement in the United States.[2] A Review of General Psychology survey, published in 2002, ranked Harlow as the 26th almost cited psychologist of the 20th century.[3]

Biography [edit]

Harry Harlow was born on October 31, 1905, to Mabel Rock and Alonzo Harlow Israel. Harlow was born and raised in Fairfield, Iowa, the third of four brothers.[iv] After a year at Reed Higher in Portland, Oregon, Harlow obtained admission to Stanford Academy through a special aptitude test. After a semester equally an English language major with nearly disastrous grades, he alleged himself as a psychology major.[5]

Harlow attended Stanford in 1924, and subsequently became a graduate student in psychology, working directly under Calvin Perry Stone, a well-known animal behaviorist, and Walter Richard Miles, a vision practiced, who were all supervised by Lewis Terman.[4] Harlow studied largely under Terman, the developer of the Stanford-Binet IQ Test, and Terman helped shape Harlow'southward hereafter. Afterward receiving a PhD in 1930, Harlow changed his proper noun from Israel to Harlow.[6] The change was fabricated at Terman's prompting for fear of the negative consequences of having a seemingly Jewish terminal name, even though his family was non Jewish.[4]

Directly after completing his doctoral dissertation, Harlow accepted a professorship at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Harlow was unsuccessful in persuading the Department of Psychology to provide him with adequate laboratory space. As a outcome, Harlow caused a vacant building down the street from the University, and, with the assistance of his graduate students, renovated the edifice into what later became known as the Primate Laboratory,[two] ane of the beginning of its kind in the world. Under Harlow's direction, information technology became a place of cutting-border research at which some 40 students earned their PhDs.

Harlow received numerous awards and honors, including the Howard Crosby Warren Medal (1956), the National Medal of Science (1967), and the Golden Medal from the American Psychological Foundation (1973). He served as head of the Human Resources Research branch of the Department of the Regular army from 1950–1952, head of the Sectionalization of Anthropology and Psychology of the National Research Council from 1952–1955, consultant to the Army Scientific Advisory Panel, and president of the American Psychological Clan from 1958–1959.

Harlow married his first wife, Clara Mears, in 1932. Ane of the select students with an IQ higher up 150 whom Terman studied at Stanford, Clara was Harlow's student before becoming romantically involved with him. The couple had ii children together, Robert and Richard. Harlow and Mears divorced in 1946. That same year, Harlow married child psychologist Margaret Kuenne. They had two children together, Pamela and Jonathan. Margaret died on 11 August 1971, after a prolonged struggle with cancer, with which she had been diagnosed in 1967.[7] Her death led Harlow to low, for which he was treated with electro-convulsive therapy.[8] In March 1972, Harlow remarried Clara Mears. The couple lived together in Tucson, Arizona, until Harlow's expiry in 1981.[two]

Monkey studies [edit]

Harlow came to the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1930[ix] after obtaining his doctorate under the guidance of several distinguished researchers, including Calvin Stone and Lewis Terman, at Stanford University. He began his career with nonhuman primate research. He worked with the primates at Henry Vilas Zoo, where he adult the Wisconsin General Testing Apparatus (WGTA) to study learning, noesis, and memory. It was through these studies that Harlow discovered that the monkeys he worked with were developing strategies for his tests. What would later become known as learning sets, Harlow described as "learning to larn."[x]

Harlow exclusively used rhesus macaques in his experiments.

In order to written report the development of these learning sets, Harlow needed access to developing primates, so he established a convenance colony of rhesus macaques in 1932. Due to the nature of his study, Harlow needed regular access to infant primates and thus chose to rear them in a nursery setting, rather than with their protective mothers.[10] This alternative rearing technique, also chosen maternal deprivation, is highly controversial to this day, and is used, in variants, as a model of early life adversity in primates.

"Nature of love" wire and material female parent surrogates

Inquiry with and caring for baby rhesus monkeys farther inspired Harlow, and ultimately led to some of his best-known experiments: the utilize of surrogate mothers. Although Harlow, his students, contemporaries, and associates presently learned how to care for the concrete needs of their baby monkeys, the nursery-reared infants remained very unlike from their female parent-reared peers. Psychologically speaking, these infants were slightly strange: they were reclusive, had definite social deficits, and clung to their fabric diapers.[10] At the same fourth dimension in the reverse configuration, babies that had grown upwards with only a mother and no playmates showed signs of fearfulness or aggressiveness.[11]

Noticing their attachment to the soft textile of their diapers and the psychological changes that correlated with the absence of a maternal figure, Harlow sought to investigate the female parent–infant bond.[x] This relationship was nether constant scrutiny in the early twentieth century, as B. F. Skinner and the behaviorists took on John Bowlby in a discussion of the mother's importance in the development of the child, the nature of their relationship, and the impact of concrete contact betwixt mother and kid.

The studies were motivated by John Bowlby'due south World Health Organization-sponsored study and report "Maternal Care and Mental Wellness" in 1950, in which Bowlby reviewed previous studies on the effects of institutionalization on child development, and the distress experienced past children when separated from their mothers,[12] such as René Spitz's[13] and his own surveys on children raised in a variety of settings. In 1953, his colleague James Robertson produced a short and controversial documentary film, titled A Two-Twelvemonth-Old Goes to Infirmary, demonstrating the well-nigh-immediate effects of maternal separation.[14] Bowlby'south report, coupled with Robertson'south film, demonstrated the importance of the primary caregiver in human and not-human primate evolution. Bowlby de-emphasized the mother'southward function in feeding equally a basis for the development of a strong female parent–child relationship, but his conclusions generated much debate. It was the debate concerning the reasons behind the demonstrated demand for maternal care that Harlow addressed in his studies with surrogates. Physical contact with infants was considered harmful to their development, and this view led to sterile, contact-less nurseries across the land. Bowlby disagreed, challenge that the mother provides much more than nutrient to the infant, including a unique bail that positively influences the child's development and mental health.

To investigate the fence, Harlow created inanimate surrogate mothers for the rhesus infants from wire and woods.[10] Each infant became attached to its detail mother, recognizing its unique face and preferring it higher up all others. Harlow next chose to investigate if the infants had a preference for bare-wire mothers or cloth-covered mothers. For this experiment, he presented the infants with a clothed female parent and a wire female parent under two weather condition. In one situation, the wire female parent held a bottle with nutrient, and the material mother held no food. In the other situation, the material mother held the bottle, and the wire mother had nothing.[10]

Overwhelmingly, the babe macaques preferred spending their time clinging to the cloth mother.[10] Even when simply the wire female parent could provide nourishment, the monkeys visited her just to feed. Harlow ended that in that location was much more than to the mother–baby human relationship than milk, and that this "contact comfort" was essential to the psychological evolution and health of infant monkeys and children. It was this enquiry that gave stiff, empirical support to Bowlby'southward assertions on the importance of love and mother–kid interaction.

Successive experiments concluded that infants used the surrogate as a base for exploration, and a source of comfort and protection in novel and even frightening situations.[15] In an experiment called the "open-field test", an baby was placed in a novel surroundings with novel objects. When the infant's surrogate mother was nowadays, information technology clung to her, just and so began venturing off to explore. If frightened, the infant ran back to the surrogate mother and clung to her for a time earlier venturing out over again. Without the surrogate mother'south presence, the monkeys were paralyzed with fear, huddling in a ball and sucking their thumbs.[15]

In the "fear examination", infants were presented with a fearful stimulus, oft a racket-making teddy bear.[15] Without the mother, the infants cowered and avoided the object. When the surrogate mother was present, however, the infant did not show great fearful responses and often contacted the device—exploring and attacking it.

Some other study looked at the differentiated effects of existence raised with merely either a wire-mother or a cloth-mother.[fifteen] Both groups gained weight at equal rates, but the monkeys raised on a wire-mother had softer stool and trouble digesting the milk, oft suffering from diarrhea. Harlow's interpretation of this behavior, which is notwithstanding widely accepted, was that a lack of contact comfort is psychologically stressful to the monkeys, and the digestive problems are a physiological manifestation of that stress.[xv]

The importance of these findings is that they contradicted both the traditional pedagogic advice of limiting or avoiding bodily contact in an endeavor to avert spoiling children, and the insistence of the predominant behaviorist school of psychology that emotions were negligible. Feeding was idea to exist the well-nigh of import factor in the formation of a mother–kid bond. Harlow ended, however, that nursing strengthened the female parent–kid bond because of the intimate body contact that it provided. He described his experiments as a report of love. He also believed that contact comfort could be provided by either mother or father. Though widely accepted now, this idea was revolutionary at the time in provoking thoughts and values apropos the studies of beloved.[16]

Some of Harlow's last experiments explored social deprivation in the quest to create an creature model for the study of depression. This written report is the most controversial, and involved isolation of babe and juvenile macaques for diverse periods of time. Monkeys placed in isolation exhibited social deficits when introduced or re-introduced into a peer group. They appeared unsure of how to interact with their conspecifics, and by and large stayed carve up from the grouping, demonstrating the importance of social interaction and stimuli in forming the ability to interact with conspecifics in developing monkeys, and, comparatively, in children.

Critics of Harlow'southward research have observed that clinging is a matter of survival in young rhesus monkeys, only not in humans, and have suggested that his conclusions, when applied to humans, overestimate the importance of contact comfort and underestimate the importance of nursing.[17]

Harlow start reported the results of these experiments in "The Nature of Beloved", the title of his address to the threescore-sixth Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association in Washington, D.C., August 31, 1958.[xviii]

Fractional and total isolation of baby monkeys [edit]

Start in 1959, Harlow and his students began publishing their observations on the effects of partial and total social isolation. Partial isolation involved raising monkeys in bare wire cages that allowed them to see, smell, and hear other monkeys, but provided no opportunity for physical contact. Full social isolation involved rearing monkeys in isolation chambers that precluded any and all contact with other monkeys.

Harlow et al. reported that partial isolation resulted in diverse abnormalities such as bare staring, stereotyped repetitive circling in their cages, and self-mutilation. These monkeys were and so observed in various settings. For the written report, some of the monkeys were kept in lone isolation for xv years.[19]

In the full isolation experiments, infant monkeys would be left alone for three, half dozen, 12, or 24[twenty] [21] months of "total social deprivation". The experiments produced monkeys that were severely psychologically disturbed. Harlow wrote:

No monkey has died during isolation. When initially removed from total social isolation, withal, they usually go into a land of emotional shock, characterized by ... autistic self-clutching and rocking. One of six monkeys isolated for 3 months refused to swallow later on release and died five days later. The autopsy study attributed death to emotional anorexia. ... The furnishings of 6 months of total social isolation were so devastating and debilitating that nosotros had assumed initially that 12 months of isolation would not produce any additional decrement. This supposition proved to exist false; 12 months of isolation almost obliterated the animals socially ...[1]

Harlow tried to reintegrate the monkeys who had been isolated for six months by placing them with monkeys who had been raised normally.[10] [22] The rehabilitation attempts met with express success. Harlow wrote that full social isolation for the kickoff six months of life produced "severe deficits in almost every aspect of social behavior".[23] Isolates exposed to monkeys the same age who were reared unremarkably "accomplished only limited recovery of simple social responses".[23] Some monkey mothers reared in isolation exhibited "acceptable maternal behavior when forced to accept baby contact over a period of months, merely showed no further recovery".[23] Isolates given to surrogate mothers developed "crude interactive patterns amidst themselves".[23] Opposed to this, when six-calendar month isolates were exposed to younger, three-month-old monkeys, they accomplished "essentially complete social recovery for all situations tested".[24] [25] The findings were confirmed by other researchers, who found no difference betwixt peer-therapy recipients and female parent-reared infants, just plant that artificial surrogates had very little effect.[26]

Since Harlow'south pioneering piece of work on touch research in development, recent work in rats has found evidence that touch on during infancy resulted in a decrease in corticosteroid, a steroid hormone involved in stress, and an increase in glucocorticoid receptors in many regions of the brain.[27] Schanberg and Field found that even curt-term pause of mother–pup interaction in rats markedly affected several biochemical processes in the developing pup: a reduction in ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) activity, a sensitive index of cell growth and differentiation; a reduction in growth hormone release (in all body organs, including the heart and liver, and throughout the brain, including the cerebrum, cerebellum, and brain stalk); an increment in corticosterone secretion; and suppressed tissue ODC responsivity to administered growth hormone.[28] Additionally, it was found that animals who are bear on-deprived have weakened immune systems. Investigators accept measured a directly, positive relationship betwixt the amount of contact and grooming an infant monkey receives during its showtime six months of life, and its ability to produce antibody titer (IgG and IgM) in response to an antibody challenge (tetanus) at a little over one year of historic period.[29] Trying to identify a mechanism for the "immunology of touch", some investigators bespeak to modulations of arousal and associated CNS-hormonal action. Touch deprivation may crusade stress-induced activation of the pituitary–adrenal system, which, in plough, leads to increased plasma cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone. Likewise, researchers propose, regular and "natural" stimulation of the skin may moderate these pituitary–adrenal responses in a positive and healthful style.[thirty]

Pit of despair [edit]

Harlow was well known for refusing to use conventional terminology, instead choosing deliberately outrageous terms for the experimental appliance he devised. This came from an early disharmonize with the conventional psychological establishment in which Harlow used the term "dearest" in place of the pop and archaically correct term "attachment". Such terms and respective devices included a forced-mating device he called the "rape rack", tormenting surrogate-mother devices he called "Iron maidens", and an isolation chamber he chosen the "pit of despair", developed past him and a graduate pupil, Stephen Suomi.

In the last of these devices, alternatively called the "well of despair", baby monkeys were left solitary in darkness for up to one year from birth, or repetitively separated from their peers and isolated in the sleeping room. These procedures quickly produced monkeys that were severely psychologically disturbed, which were used as models of human low.[31]

Harlow tried to rehabilitate monkeys that had been subjected to varying degrees of isolation using various forms of therapy. "In our study of psychopathology, nosotros began as sadists trying to produce abnormality. Today, nosotros are psychiatrists trying to achieve normality and equanimity."[32] : 458

Criticism [edit]

Many of Harlow's experiments are at present considered unethical—in their nature too as Harlow's descriptions of them—and they both contributed to heightened awareness of the treatment of laboratory animals, and helped propel the cosmos of today's ethics regulations. The monkeys in the experiment were deprived of maternal affection, potentially leading to what are now known as panic disorders.[33] University of Washington professor Factor Sackett, one of Harlow's doctoral students, stated that Harlow's experiments provided the impetus for the animal liberation movement in the U.Due south.[two]

William Bricklayer, another one of Harlow's students who connected conducting deprivation experiments subsequently leaving Wisconsin,[34] has said that Harlow "kept this going to the signal where it was clear to many people that the work was actually violating ordinary sensibilities, that everyone with respect for life or people would observe this offensive. It'southward as if he sat down and said, 'I'm only going to exist around some other 10 years. What I'd like to do, and then, is leave a great big mess behind.' If that was his aim, he did a perfect job."[35]

Stephen Suomi, a former Harlow pupil who at present conducts maternal deprivation experiments on monkeys at the National Institutes of Health, has been criticized past PETA and members of the U.South. Congress.[36] [37]

Yet another of Harlow's students, Leonard Rosenblum, also went on to bear maternal deprivation experiments with bonnet and pigtail macaque monkeys, and other research, involving exposing monkeys to drug–maternal-deprivation combinations in an try to "model" human panic disorder. Rosenblum's enquiry, and his justifications for information technology, have likewise been criticized.[33]

Theatrical portrayal [edit]

A theatrical play, The Harry Harlow Project, based on the life and work of Harlow, has been produced in Victoria and performed nationally in Commonwealth of australia.[38]

Timeline [edit]

| Year | Event |

| 1905 | Born Oct 31 in Fairfield, Iowa, Son of Alonzo and Mabel (Stone) Israel |

| 1930–44 | Staff, University of Wisconsin–Madison Married Clara Mears |

| 1939–xl | Carnegie Fellow of Anthropology at Columbia Academy |

| 1944–74 | George Cary Comstock Research Professor of Psychology |

| 1946 | Divorced Clara Mears |

| 1948 | Married Margaret Kuenne |

| 1947–48 | President, Midwestern Psychological Association |

| 1950–51 | President of Division of Experimental Psychology, American Psychological Association |

| 1950–52 | Head of Human Resources Inquiry Branch, Section of the Regular army |

| 1953–55 | Head of Division of Anthropology and Psychology, National Research Quango |

| 1956 | Howard Crosby Warren Medal for outstanding contributions to the field of experimental psychology |

| 1956–74 | Director of Primate Lab, University of Wisconsin |

| 1958–59 | President, American Psychological Clan |

| 1959–65 | Sigma 11 National Lecturer |

| 1960 | Distinguished Psychologist Award, American Psychological Clan Messenger Lecturer at Cornell University |

| 1961–71 | Director of Regional Primate Enquiry Center |

| 1964–65 | President of Sectionalization of Comparative & Physiological Psychology, American Psychological Association |

| 1967 | National Medal of Science |

| 1970 | Death of his spouse, Margaret |

| 1971 | Harris Lecturer at Northwestern University Remarried Clara Mears |

| 1972 | Martin Rehfuss Lecturer at Jefferson Medical College Gold Medal from American Psychological Foundation Annual Accolade from Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality |

| 1974 | Academy of Arizona (Tucson) Honorary Research Professor of Psychology |

| 1975 | Von Gieson Award from New York State Psychiatric Plant |

| 1976 | International Award from Kittay Scientific Foundation |

| 1981 | Died December half dozen |

Early on papers [edit]

- The outcome of large cortical lesions on learned behavior in monkeys. Science. 1950.

- Retention of delayed responses and proficiency in oddity problems past monkeys with preoccipital ablations. Am J Psychol. 1951.

- Discrimination learning past normal and brain operated monkeys. J Genet Psychol. 1952.

- Incentive size, nutrient deprivation, and nutrient preference. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1953.

- Effect of cortical implantation of radioactive cobalt on learned behavior of rhesus monkeys. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1955.

- The effects of repeated doses of total-body x radiation on motivation and learning in rhesus monkeys. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1956.

- The pitiful ones: Studies in depression "Psychology Today". 1971

References [edit]

- ^ a b Harlow, H. F.; Dodsworth, R. O.; Harlow, M. Thousand. (June 1965). "Total social isolation in monkeys". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences of the United States of America. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 54 (one): 90–97. Bibcode:1965PNAS...54...90H. doi:x.1073/pnas.54.ane.90. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC285801. PMID 4955132.

- ^ a b c d Blum, Deborah (2002). Beloved at Goon Park: Harry Harlow and the Science of Affection. Perseus Publishing. p. 225.

- ^ Haggbloom, Steven J.; Powell, John 50., 3; Warnick, Jason E.; Jones, Vinessa K.; Yarbrough, Gary L.; Russell, Tenea M.; Borecky, Chris M.; McGahhey, Reagan; et al. (2002). "The 100 virtually eminent psychologists of the 20th century". Review of General Psychology. 6 (ii): 139–152. CiteSeerXx.1.1.586.1913. doi:ten.1037/1089-2680.vi.2.139. S2CID 145668721.

- ^ a b c McKinney, William T (2003). "Honey at Goon Park: Harry Harlow and the Science of Affection". American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (12): 2254–2255. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2254.

- ^ Suomi, Stephen J. (8 Baronial 2008). "Rigorous Experiments on Monkey Beloved: An Account of Harry F. Harlow's Role in the History of Attachment Theory". Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science. 42 (4): 354–69. doi:ten.1007/s12124-008-9072-9. PMID 18688688.

- ^ Rumbaugh, Duane G. (1997). "The psychology of Harry F. Harlow: A bridge from radical to rational behaviorism". Philosophical Psychology. 10 (ii): 197. doi:x.1080/09515089708573215.

- ^ Blum, Deborah (2011). Love at Goon Park: Harr Harlow and the science of affection. New York: Basic Books. p. 228. ISBN9780465026012.

- ^ "Keith E Rice - Zipper in Infant Monkeys". Archived from the original on 2012-06-01. Retrieved 2012-05-01 . Key study: attachment in baby monkeys

- ^ Van De Horst, Frank (2008). "When Strangers Meet": John Bowlby and Harry Harlow on Attachment Behavior". Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science. 42 (4): 370–388. doi:10.1007/s12124-008-9079-2. PMID 18766423.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Suomi, S. J.; Leroy, H. A. (1982). "In memoriam: Harry F. Harlow (1905–1981)". American Journal of Primatology. 2 (4): 319–342. doi:ten.1002/ajp.1350020402. PMID 32188173.

- ^ "A Science Odyssey: People and Discoveries: Harry Harlow". PBS.

- ^ Mcleod, Saul (Feb five, 2008). "Attachment Theory". Simply Psychology.

- ^ Spitz, R. A.; Wolf, One thousand. Thousand. (1946). "Anaclitic depression: an inquiry into the genesis of psychiatric conditions in early childhood. II". Psychoanalytic Study of the Child. ii: 313–342. doi:10.1080/00797308.1946.11823551. PMID 20293638.

- ^ Robert, Karen (February 1990). "Condign attached" (PDF). The Atlantic Monthly. 265 (two): 35–70. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 Dec 2010. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Harlow, Harry F. (1958). "The nature of love" (PDF). American Psychologist. American Psychological Association (APA). thirteen (12): 673–685. doi:10.1037/h0047884. ISSN 0003-066X.

- ^ Rumbaugh, Duane (June 1997). "The psychology of Harry F. Harlow: A bridge from radical to rational behaviorism". Philosophical Psychology. 10 (ii): 197–210. doi:10.1080/09515089708573215.

- ^ Mason, W.A. (1968). "Early on social deprivation in the nonhuman primates: Implications for human being behavior". In D. C. Drinking glass (ed.). Environmental Influences. New York: Rockefeller University and Russell Sage Foundation. pp. 70–101.

- ^ Green, Christopher D. (March 2000). "The Nature of Love". Classics in the History of Psychology.

- ^ A variation of this housing method, using cages with solid sides as opposed to wire mesh, but retaining the 1-cage, one-monkey scheme, remains a common housing practice in primate laboratories today. Reinhardt, V; Liss, C; Stevens, C (1995). "Social Housing of Previously Single-Caged Macaques: What are the options and the Risks?". Animal Welfare. Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. 4: 307–328.

- ^ Harlow, H.F. (1962). "Development of affection in primates". In Bliss, E.50. (ed.). Roots of Beliefs. New York: Harper. pp. 157–166.

- ^ Harlow, H.F. (1964). "Early social deprivation and later on behavior in the monkey". In A.Abrams; H.H. Gurner; J.Due east.P. Tomal (eds.). Unfinished tasks in the behavioral sciences. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. pp. 154–173.

- ^ Suomi, SJ; Delizio, R; Harlow, HF (1976). "Social rehabilitation of separation-induced depressive disorders in monkeys". American Journal of Psychiatry. American Psychiatric Association Publishing. 133 (11): 1279–1285. doi:10.1176/ajp.133.11.1279. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 824960.

- ^ a b c d Harlow, Harry F.; Suomi, Stephen J. (1971). "Social Recovery by Isolation-Reared Monkeys". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the Usa of America. 68 (seven): 1534–1538. Bibcode:1971PNAS...68.1534H. doi:x.1073/pnas.68.7.1534. PMC389234. PMID 5283943.

- ^ Harlow, Harry F.; Suomi, Stephen J. (1971). "Social Recovery by Isolation-Reared Monkeys". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences of the U.s.a.. 68 (7): 1534–1538. Bibcode:1971PNAS...68.1534H. doi:10.1073/pnas.68.7.1534. PMC389234. PMID 5283943.

- ^ Suomi, Stephen J.; Harlow, Harry F.; McKinney, William T. (1972). "Monkey Psychiatrists". American Journal of Psychiatry. 128 (eight): 927–932. doi:x.1176/ajp.128.viii.927. PMID 4621656.

- ^ Cummins, Marking S.; Suomi, Stephen J. (1976). "Long-term furnishings of social rehabilitation in rhesus monkeys". Primates. 17 (1): 43–51. doi:10.1007/BF02381565. S2CID 1369284.

- ^ Jutapakdeegul, N.; Casalotti, Stefano O.; Govitrapong, P.; Kotchabhakdi, North. (v November 2017). "Postnatal Touch Stimulation Acutely Alters Corticosterone Levels and Glucocorticoid Receptor Cistron Expression in the Neonatal Rat". Developmental Neuroscience. 25 (1): 26–33. doi:10.1159/000071465. PMID 12876428. S2CID 31348253.

- ^ Schanberg, S; Field, T. (1988). "Maternal deprivation and supplemental stimulation". In Field, T; McCabe, P; Schneiderman, Due north (eds.). Stress and Coping Across Evolution. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- ^ Laudenslager, ML; Rasmussen, KLR; Berman, CM; Suomi, SJ; Berger, CB (1993). "Specific antibody levels in free-ranging rhesus monkeys: relationships to plasma hormones, cardiac parameters, and early behavior". Developmental Psychology. 26 (7): 407–420. doi:10.1002/dev.420260704. PMID 8270123.

- ^ Suomi, SJ. "Touch and the immune organization in rhesus monkeys". In Field, TM (ed.). Bear on in Early Evolution. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc.

- ^ Suomi, JS (1971). Experimental production of depressive behavior in young monkeys (Doctoral thesis.). Academy of Wisconsin–Madison.

- ^ Harlow, H. F.; Harlow, K. Thou.; Suomi, S. J. (September–October 1971). "From thought to therapy: lessons from a primate laboratory" (PDF). American Scientist. 59 (5): 538–549. Bibcode:1971AmSci..59..538H. PMID 5004085.

- ^ a b "A Critique of Maternal Deprivation Monkey Experiments at The State University of New York Health Science Center". Medical Research Modernization Committee. Archived from the original on Oct 23, 2007.

- ^ Capitanio, John P.; Mason, William A. (2000). "Cognitive style: Problem solving by rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) reared with living or inanimate substitute mothers". Journal of Comparative Psychology. American Psychological Clan (APA). 114 (2): 115–125. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.114.2.115. ISSN 1939-2087. PMID 10890583.

- ^ Blum, Deborah (1994). The Monkey Wars. Oxford University Printing. p. 96.

- ^ Firger, Jessica. "Questions raised well-nigh mental health studies on baby monkeys at NIH labs". CBSNew.com. CBS. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ Novak, Bridgett (2014-12-25). "Fauna enquiry at NIH lab challenged by members of Congress". Reuters . Retrieved half dozen January 2015.

- ^ "The Harry Harlow Project". The Age: Arts Review. 30 November 2009. Retrieved 12 Baronial 2011.

Further reading [edit]

- Harlow, Harry (1958). "The nature of love". American Psychologist. 13 (12): 673–685. doi:10.1037/h0047884.

- Harry Harlow: Monkey Beloved Experiments – Adoption History

- Harry Harlow – A Scientific discipline Odyssey: People and Experiments

- Harlow (July 1965). "Full social isolation in monkeys". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 54 (1): ninety–97. Bibcode:1965PNAS...54...90H. doi:10.1073/pnas.54.1.xc. PMC285801. PMID 4955132.

- Harry Harrow's Studies – YouTube mix playlist of eleven video documentaries

- "A History of Primate Experimentation at the University of Wisconsin, Madison".

- Blum, Deborah. Love at Goon Park: Harry Harlow and the Science of Amore. Perseus Publishing, 2002. ISBN 0-7382-0278-nine

- Monkey love – commodity about Harlow'south piece of work in the Boston Globe

External links [edit]

- National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

levasseurwhest1969.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Harlow

0 Response to "Which of the Following Can Be Concluded From Harry Harlow's Research With Rhesus Monkeys?"

Post a Comment